Ultramarine Blue Pigment: Unveiling Its Timeless Beauty and Scientific Wonders

Unlike many pigments that fade over time, ultramarine’s molecular structure makes it remarkably stable and resistant to light and chemicals. This durability has preserved the vibrancy of ancient artworks, allowing us to witness the same vivid blue that inspired artists centuries ago.

Examinations of easel paintings and illuminated manuscripts have shown that natural ultramarine retains its integrity remarkably well, even in several centuries-old artworks. Generally, ultramarine is recognized for its permanence as a pigment. Despite being a sulfur-containing compound, which typically releases sulfur as hydrogen sulfide, it has historically been combined with lead white without any significant incidents of the lead pigment darkening to form lead sulfide.

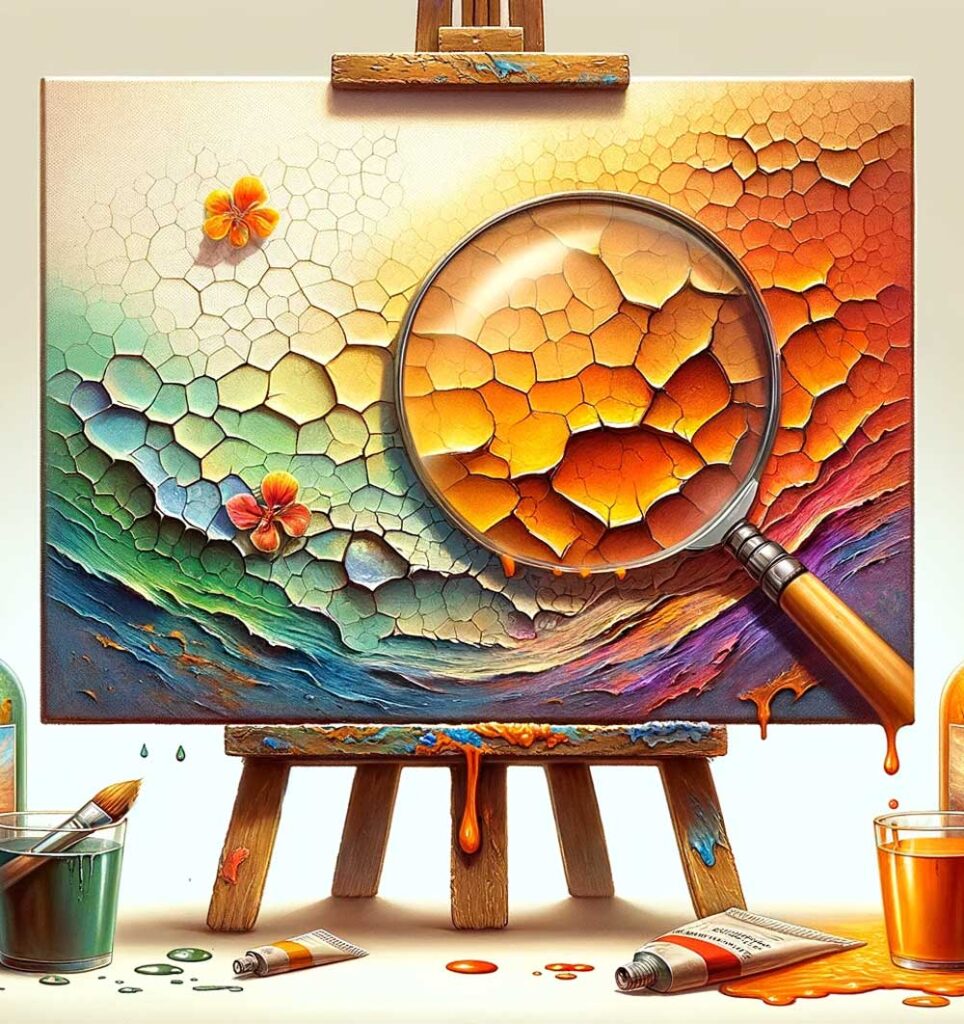

However, a condition known as “ultramarine sickness” has occasionally been observed, particularly in oil paintings. This manifests as a grayish or yellowish-gray discoloration on the surface of the pigment. Such occurrences are more common with synthetic ultramarine, especially in industrial uses. The exact cause of this discoloration is a subject of debate among conservation scientists. Possible factors include exposure to atmospheric sulfur dioxide and moisture, the acidity of an oil- or oleo-resinous paint medium, or the protracted drying of the oil, during which water absorption might lead to swelling, increased opacity of the medium, and consequently, whitening of the paint film.

Under normal conditions, synthetic ultramarine demonstrates considerable permanence. Lightfastness testing has confirmed its robustness to light exposure. However, it is notably susceptible to acidic environments. In urban settings with high concentrations of sulfur dioxide or similar acidic emissions, there have been instances where ultramarine blue used in outdoor posters has experienced fading. A notable occurrence of “ultramarine sickness” in synthetic ultramarine on a 20th-century painting was recorded, but the fading of the paint film was primarily attributed to the deterioration of the paint medium rather than the pigment itself. Investigations conducted by Wagner and Mertz in 1930 revealed that ultramarine can be safely combined with white lead, avoiding chemical reaction, as long as the white lead contains minimal lead acetate and the paint medium maintains a low level of acidity.

Both natural and synthetic ultramarine exhibit stability in alkalis under normal conditions. However, synthetic ultramarine can fade when in contact with lime (calcium oxide), such as in the coloring of concrete or plaster. These findings have prompted experts to consider whether the fading of the natural pigment in fresco paintings could be due to interaction with lime plaster.

Image: Ultramarine Madness, Eric Johnson, oil on panel, 53.4 cm × 48.3 cm (21.0 in × 19.0 in), Boston, MA, Private Collection

Read more: Natural Pigments, Ultramarine Blue

Responses