Exploring the 18th-Century Painting Palette, Techniques and Materials

In 18th-century art, adherence to the structured guidelines promulgated by the esteemed French Academy, founded in 1648, was paramount. This adherence was notably manifest in the meticulous organization of the painter’s palette, a practice that underwent minimal alteration throughout the century. The investigation by F. Schmid in his paper aims to delineate the progression and the nuanced aspects of the painter’s tools during this era, with a particular emphasis on the palette. By examining the pigments, palette arrangement, and auxiliary tools employed by artists from Chardin to Trumbull, we uncover the intricate interplay between material innovation and artistic expression.

The traditional palette configuration in the 18th century featured a simple array of pigments, predominantly earth colors, arrayed from white at the palette’s right edge (nearest the thumb-hole) to black at the extreme left. This arrangement facilitated a systematic approach to color application, essential for the foundational layers of painting. Notably, expensive pigments like vermilion were placed near the thumb-hole, reflecting both their cost and specialized use in detailing, particularly in flesh tones. This strategic placement underscores the economic considerations that subtly influenced artistic practices.

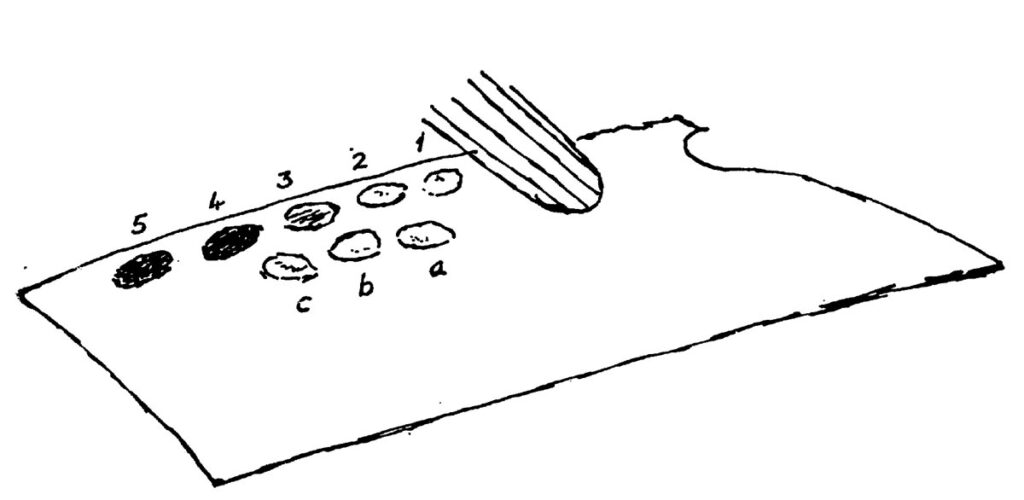

The author depicts Chardin’s palette of 1765. There are two rows of colors. In the first position nearest the thumbhole is Flake white; 2. Yellow ochre; 3. Light red; 4. Ivory black; 5. Burnt umber. In the second row are a. Prussian blue; b. Naples yellow; c. Vermilion, and eight brushes in the thumbhole of the palette.

The analysis of specific palettes used by artists such as J.B.S. Chardin and Jean-Baptiste van Loo reveals a minimal but purposeful selection of colors. Chardin’s palette, for instance, exemplified restraint with five basic pigments and a secondary column for primary colors, signifying a balance between simplicity and the necessity for a broader color spectrum in more intricate compositions. Van Loo’s palette, on the other hand, demonstrated a slightly more extensive range with nine pigments, accommodating a broader palette for flesh tones and highlights. This variance illustrates the individual artist’s approach to color theory and application within the confines of academic conventions.

Furthermore, examining artists’ implements extends beyond palettes to include brushes and mediums, revealing a preference for hog-hair and sable-hair brushes for their varying textures and applications. Van Loo’s use of a mahlstick, for instance, emphasizes the ergonomic considerations artists made to maintain precision over long periods.

As we progress through the century, a shift from square to oval palettes is observed, indicating a subtle evolution in ergonomic design and perhaps a broadening of the color spectrum used by artists. This evolution reflects a nuanced response to changing aesthetic sensibilities and the practical demands of painting techniques.

The consistent use of earth tones across various artists’ palettes underscores a reliance on these pigments for their stability and versatility. Despite the emergence of new pigments and colors, the foundational role of earth tones remained unchallenged, serving as a testament to the enduring principles of color theory as applied in the 18th century.

The detailed study of palettes and painting implements of the 18th century reveals a fascinating interplay between tradition and innovation. While artists adhered to the structured guidelines established by the French Academy, their individual choices and adaptations of these tools underscore a dynamic engagement with the materials of their craft. The evolution of painting implements during this period not only reflects the practical considerations of color application and ergonomic design but also signifies the broader artistic and cultural shifts that characterized 18th-century art.

To learn more read F. Schmid. “The Painter’s Implements in Eighteenth-Century Art.” The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 108, No. 763 (Oct, 1966), pp. 519-521. https://www.jstor.org/stable/875160

Responses